Some ill and disabled people are so worried about the process, they are using mobile phones to secretly record those interviews, critics say.

Daily Archives: 15/10/2017

What If The 1987 Great Storm Happened Today?

When Michael Fish presented the BBC Weather forecast on the 15th October he had already been a regular fixture on television for 13 years. After all those years and the hundreds of weather broadcasts he will have recorded, it’s his opening remarks on this lunchtime forecast that are still replayed 30 years later.

“Good afternoon to you. Earlier on today apparently, a woman rang the BBC and said she heard there was a hurricane on the way. Well, if you’re watching don’t worry, there isn’t…”

[embedded content]

That night, the British Isles was hit by its worst storm since 1703. 22 lives were lost across Britain and France. Hundreds of thousands of homes were left without power, with destructive winds bringing down 15 million trees and blocking many roads and railways with wreckage. The cost of devastation from the Great Storm rose to £1 billion.

Strictly speaking, Mr Fish was correct: The Great Storm wasn’t technically a hurricane. Hurricanes, by definition, are tropical cyclones fuelled by seas warmer than 26 °C. This was an extratropical cyclone – otherwise known as a mid-latitude depression. The main differences are to do with where they form, how they are fuelled and their structure.

For those hit by the Great Storm, these technical differences won’t matter. The Great Storm was as terrifying and – with sustained wind speeds near Eastbourne of 87 mph – as powerful as a category one hurricane.

The original hand-drawn charts from the 15th and 16th October 1987. Credit: Met Office.

Incredibly, the public were not warned of what was to come – even in the hours before it struck. Nowadays, we have instant access to weather forecasts online and through our mobile apps as well as continuous updates via social media. It’s difficult to imagine going to bed in the evening completely unaware of an imminent hurricane-force storm in the English Channel. But would we really do a better job in 2017 compared to 1987?

A comparison of the technological progress between 1987 and 2017 demonstrates just how far we’ve come during the past three decades. In 1987 the Met Office supercomputer could only perform 4 million calculations per second. Modern smartphones can perform around a thousand times that number of instructions per second.

Of course, these are dubious comparisons; smartphones are not designed to run computer weather prediction models. But 2017’s weather computers are billions of times more powerful than 1987’s. The current Met Office Cray XC40 computer can run a mind-boggling 14 thousand trillion calculations per second, equivalent to 2 million calculations every second for every human on the planet.

Met Office supercomputer. Credit: Met Office.

Powerful supercomputers can handle more data. One failing in 1987 was the lack of weather observations – just 1200 – to represent the current weather across the whole planet. If we don’t know the current state of the atmosphere, how can we accurately predict its future state? In 2017, 215 million weather observations are fed into the supercomputer with the majority of these arriving from satellites allowing an uninterrupted view of the entire world.

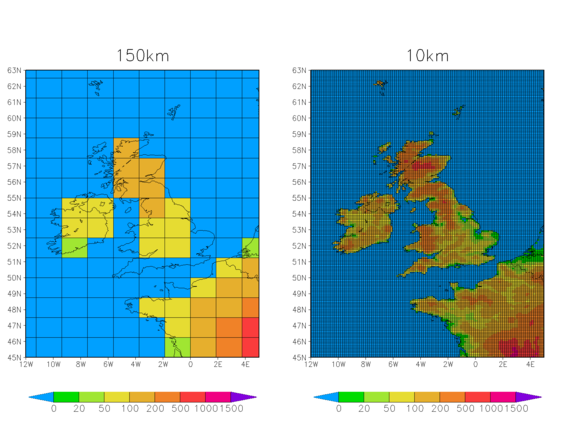

To turn weather observations into reliable forecasts, the Met Office runs high-resolution computer models. In 1987, the resolution for the Met Office ‘coarse grid mesh’ global model was 150 km with a so-called ‘fine grid mesh’ at 80 km resolution covering the North Atlantic and Europe. Now, the global model is 10 km and the UK is covered by a 1.5 km grid.

Credit: Met Office. A comparison of the global computer model resolution in 1987 and 2017.

Perhaps most importantly, in modern weather forecasting the computer doesn’t just run one simulation – it runs many. Each computer model run is tweaked very slightly at the outset to account for the fact that small errors in the forecast on day one can escalate into very large errors by day three.

This is called ensemble weather prediction and it can provide us with a range of outcomes along with the probability of them occurring. If applied to the Great Storm, it might have given weather forecasters an idea of worst-case scenarios and their relative likelihoods.

The enormous increase in computing power and forecasting capability has made a difference. The Met Office four-day weather forecasts are now as accurate as the 1987 one-day forecast. But this would all be meaningless if we still failed to warn people of severe weather.

As a direct result of the Great Storm, the National Severe Weather Warning Service was established, providing a means for alerting the government, emergency services and the public of weather that poses a risk to life and property.

Initially, these warnings were faxed and broadcast on radio and television. When Michael Fish presented his infamous forecast, most people were provided weather forecasts at fixed times through the day. Today, over 90% of adults see weather information through a range of channels including the web, social media and mobile apps.

In recent years, the Met Office has begun naming storms that have the potential to cause significant impacts to the British Isles. Now, whenever the Met Office names a storm it soon becomes a trending topic on Facebook and Twitter, increasing awareness of potential severe weather and allowing people to make decisions that could save their lives.

[embedded content]

If the Great Storm happened today, it’s highly likely ensemble computer modelling would at the very least highlight a risk of hurricane-force winds in the English Channel. A risk of such significant weather would be enough for the Met Office to start issuing severe weather warnings and name the storm. Continuous updates on television, radio, online and through social media would increase awareness in the days ahead of impact. Lives could be saved.

NHS patients to be asked about sexuality

NHS England says the question will deter discrimination against lesbian, gay and bisexual people.

Health24.com | 5 reasons sweat is your best friend on the bike

Sweat might seem like just a sticky issue, but it’s so much more than the reason no one hugs you after a ride.

In reality, sweat is your body’s sprinkler system: Heat up enough, and the waterworks activate to help you stay cool and keep hammering down the road.

The hotter it gets, the more efficient sweating becomes the key to success.

Here’s what you need to know to embrace your natural coolant and make it work for you.

1. The fitter you are, the faster you sweat

Most of us begin to sweat when our core temperatures rise about 0.3 degrees Celcius above normal, says Dr Caroline Smith, director of the Thermal and Microvascular Physiology Laboratory at an American University.

As you get fitter, your body becomes more efficient at cooling itself. “Well-trained athletes begin sweating at a lower core temperature, and they sweat more,” Dr Smith says.

Your body also starts sweating nearly immediately when you launch into a sprint or hard effort in the heat, Dr Smith says. In those cases, your body doesn’t even wait to heat up: It knows what’s coming.

2. You need to drink (almost) as much as you sweat to stay cool

The human body makes sweat from blood plasma (the watery part of your blood). If you want to keep sweating – and you do – you need to hydrate well enough to prevent your blood from turning to sludge.

How much you need to drink depends on how much you’re pouring out. This amount varies widely from rider to rider depending on a host of factors, including, of course, how hot it is.

In one study of 26 cyclists competing in a 164km road race, sweat losses ranged from 4.9 to 12.7 litres.

You can’t – and shouldn’t try to – replace every drop of sweat you lose, but you need to stay reasonably hydrated.

Research shows that about 590ml of fluid an hour does the trick for the average cyclist. Bigger riders may need more, smaller riders may need less, and everyone may need a bit more when it’s really hot. Your thirst is a good guide.

In order to hydrate while exercising, it’s important to drink fluids that contain a little sugar and salt (most sports drinks contain both). Both help pull fluid from your intestines and into your bloodstream more quickly, making fluid readily useable for sweat.

Your body also loses electrolytes like salt through sweat while drawing water to the surface of your skin, and the salts need to be replaced.

3. Women sweat less and usually run hotter

Women typically sweat less than men. If you’re premenopausal, you also have a higher core body temperature and significantly lower blood plasma volume during the high-hormone days before your period.

A little chicken broth, miso soup or sodium-heavy hydration beverage can help pull the fluid back into your bloodstream where you need it to sweat.

4. Sweat needs to evaporate to cool you

Pouring buckets of sweat doesn’t do you much good if it just soaks your clothes and sits on your skin. The cooling response is a result of evaporation, which happens as your body unloads heat energy while helping the sweat turn gaseous.

That’s why it often feels harder biking in humid conditions. It’s also why it’s important to wear wicking materials that pull sweat from your skin through the material and into the air.

5. Train your sweat response

Just as your sweat rate changes as you get fitter, it also adjusts to heat, says exercise physiologist Dr Stacy Sims.

“As you acclimate to the heat, your total blood volume increases, and your heart rate and body temperature get lower at any given exertion. You start sweating earlier and sweat more, so you can better cool yourself. The composition of your sweat changes, so you lose fewer electrolytes as you sweat. All are key for sustaining exercise in the heat,” she says.

Heading somewhere hot from somewhere not for a big event? Unless you can go ahead of time to acclimate, you can do some DIY heat acclimatisation wherever you live.

Simply wearing more clothes and using fewer fans on your trainer can help your body prepare for being in a hot environment. Just be sure everything is breathable and don’t overdo it.

You want to simulate a hot environment but not give yourself heat illness. You can also use hot yoga or a sauna, says Dr Sims. But you need to be consistent for about five days in a row to get a benefit.

This article was originally published on www.bicycling.co.za

Image credit: iStock

NEXT ON HEALTH24X