The first time I was in China, I became one of her lost girls. As I was taken from my birth mother’s arms and placed at a nearby train station, I became a statistic ― another baby uprooted by the country’s one-child policy. At 11 months old, I was plucked from China’s embrace and placed into that of my parents. My roots began to grow in the soil of a different land.

When I was old enough to comprehend the gravity of my truth, my parents sat me down and told me that I had been adopted from China. This supposed revelation did not alter the trajectory of my life as my parents feared it might. It was fairly easy, even as a child, to recognise that I did not look like those around me, especially my parents. In fact, I found it quite awesome to be different ― to have come from a country so rich with history and culture.

Advertisement

However, the reality of living in a town with a predominantly white population is that many of its residents ostracise anyone who is different. I tried desperately to fit in with the other kids, but it became clear early on that despite my parents’ whiteness, my Chineseness would always make me an outsider.

Growing up, I listened as friends discussed which parent they resembled the most, and I grappled with the guilt that came with wishing I could participate in those discussions. I laughed along with others as they asked me to talk to them in “my language” and proceeded to speak gibberish in a way that was supposed to imitate Mandarin. For years, I didn’t know how to feel, or if my feelings were even valid. I didn’t realise that these seemingly small acts of aggression were racist and that they would grow into hatred in the future.

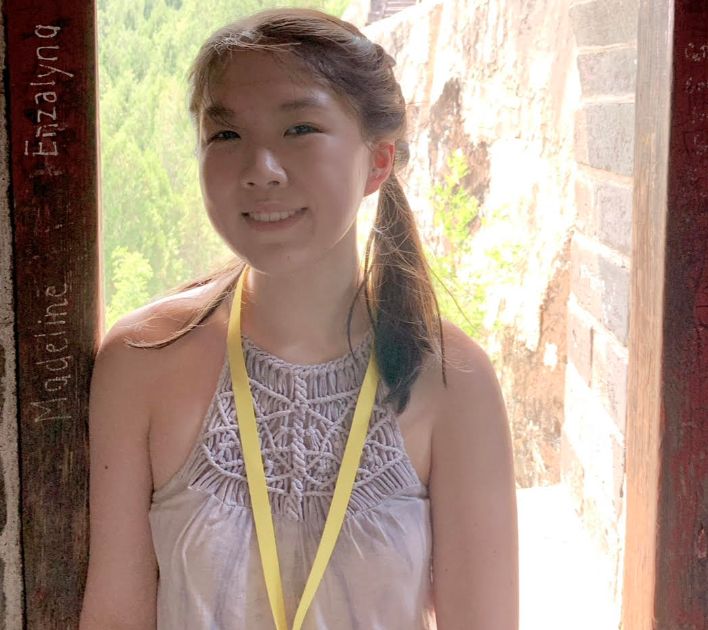

Courtesy of Iris Anderson

The first time I returned to China with my parents, I was 9 years old and longing for a place filled with people who looked like me. I was completely in awe of the country that created me, and this is when I first realised that I needed to embrace being Chinese. This proved nearly impossible. It was obvious that I did not belong to those who lived in China. From the way I dressed to the language that I spoke ― or couldn’t speak ― to them, I was American through and through.

Advertisement

As the trip went on, I found myself becoming increasingly disconnected from China and Chinese culture. I felt like a foreigner in a country that I desperately believed should have felt like home. This was the revelation that changed the trajectory of my life: My identity as a transracial adoptee seemed to define me everywhere I went. I was too Chinese to be American in America, and I was too American to be Chinese in China.

As I grew older, it became more common for adults to ask me how lucky I felt to be adopted from China, and I became resentful at how their questions commodified me. If I did not respond with gratitude for being adopted, it was as if a switch flipped in their mind and they saw me as a selfish girl who owes her parents everything. I left an abundance of words unsaid. To these people, this topic seemed clearly black and white: I was adopted from China after being left at a train station and should be grateful for my parents’ generosity ― for the roof they put over my head and the food they put on my plate.

Obviously, I love my parents. They have given so much to me and I would not be where I am today without them. My epiphany occurred when I realised that I am allowed to simultaneously love my parents and grieve what I lost. While transracial adoptees may be placed into amazing, loving families, it does not change the fact that their culture was stolen from them.

I have always belonged to an in-between place: not quite Chinese, but definitely not white either. The spaces and resources available to transracial adoptees are few and far between despite how large our population is, especially in the United States. My parents never hid the fact that I was Chinese, and they did the best that they could to expose me to Chinese traditions, but their efforts had their limits. Still, I am lucky to have parents who wanted and pushed for me to be connected to the country in which I was born.

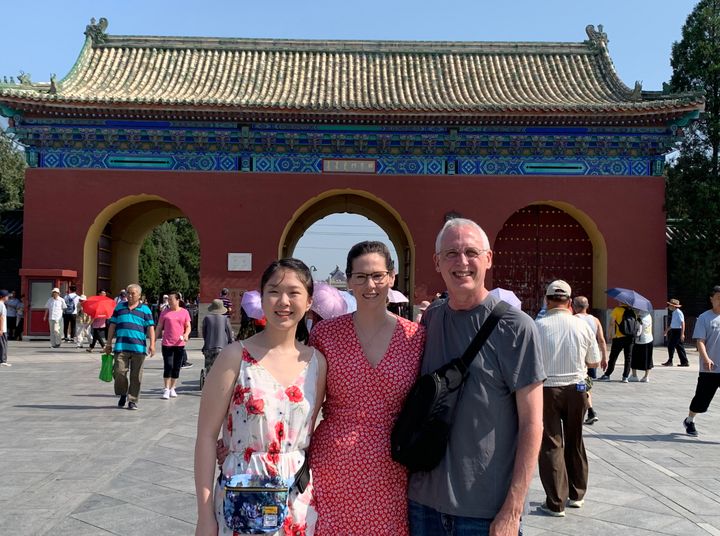

Courtesy of Iris Anderson

Advertisement

When I came to them about wanting to feel more connected to China and Chinese culture, they searched for years to find someone who could teach me Chinese. Unfortunately this task proved immensely difficult, so instead I began teaching myself the basics. My parents promised to take me back to China as soon as possible, especially now that I was older and could understand the importance of the trip a little bit more. They could tell I was struggling to reconcile my identities and always made sure that I knew I could lean on them for support. Unlike others, my parents never held my emotions against me and were ― and still are ― pillars of support.

The second time I returned to China, I was 15 and felt more in touch with my emotions. I wanted to build connections with other adoptees and hear their stories. This trip, which catered to adoptees from the same agency, allowed me to spend time with others who had been taken into white families.

Together, we found and created a safe environment for each other where we could talk about our experiences and vent our emotions without fear of judgment. This visit was different for me. I felt seen and heard by others who experienced the same inner turmoil that I had. Together we laughed and cried and lamented what could have been. In another life, would we have been able to meet under different circumstances?

It didn’t matter, we answered. We realised that all that mattered was what we had now, a fragmented past blended with a found family, each other included. While we didn’t all have the same goals for our return to China, we did share one: to reconcile our guilt and our curiosity. For me, I held no anger toward my birth mom for giving me up, especially when I understood the state of China and the one-child policy. But the curiosity of knowing about where and who I came from was there, and probably always will be. By the end of the trip, I cannot say that this goal was completely achieved. But while it might sound cliche, we adoptees did find each other, and in some way that was worth more to us than our original goals.

When I returned to the United States, I finished high school with a different perspective than the one I entered with. I felt able to embrace my in-between identity and reconcile the parts of me that had always felt at odds. Still, I lean on those I have found on my journey and continue to search for others who help me feel whole.

Advertisement

Courtesy of Iris Anderson

All transracial adoptees deserve to have a place where they can release their emotions and feel a sense of community. While I know not all transracial adoptees will want or be able to return to their country of birth and connect with others who have shared experiences, I hope they can find another way to build a community, perhaps through local groups or online. Being able to share my thoughts, emotions and challenges ― which I worried only I was thinking, feeling and facing ― with people like me has changed my life for the better.

It has been a difficult adventure to reach a place where I feel comfortable with who I am ― Chinese, American and an adoptee ― but it has allowed me not only to deepen my roots, but also to make flowers bloom in my life today.

Iris Anderson is studying biology and psychology at Columbia University and is part of the class of 2026. She loves to write in her free time and is inspired by her personal experiences and those around her. Iris would like to thank her University Writing professor, Emily Weitzman, and her Literature Humanities professor, Taarini Mookherjee, for their support of her writing endeavours.