The elevator doors opened to reveal a woman who also appeared to be in her mid-20s. Pausing for her to step out, I noticed that she was wearing a button pinned on her shirt. It read, “Be kind to me. I’m grieving.”

As she moved past me, I wanted to stop her. I wanted to reach out with a gesture or words that would capture her attention. I wanted to let her know that I understood, to explain that my mom had died earlier that year, to tell her that I knew what it was to grieve. But before I had the chance, she was walking across the lobby and through the building’s automatic doors, so I stepped into the elevator, thinking about the loss I always carried with me and wondering what it felt like for her to carry a loss too.

Advertisement

At that time, my grief was still so fresh and so heavy. It was still hard to put it into words, to make others understand, and, as the elevator rose, I remember envying that stranger’s button, the way she so easily communicated to the rest of the world that her world had been forever changed. I needed to be able to do that, to help others to see my grief. I didn’t know if it would lessen the weight of it, but I thought that it might make it feel less consuming. Maybe it would help me process what the rest of my life would look like without my mom in it. Maybe doing so would be able to make me feel less alone.

Dan Levy’s new Netflix film, Good Grief, which he wrote, produced, directed and stars in, does all of the things that I wished I could have done for myself back then; it makes grief tangible.

The movie opens as if it’s a holiday film instead of a drama. Ella Fitzgerald’s Sleigh Ride plays as the first shot, a beautiful London townhouse decorated for Christmas and filled with people, appears on the screen. Inside, Marc (Dan Levy) is talking to his friend Thomas (Himesh Patel). It quickly becomes evident through Thomas’ simultaneously entertaining and self-deprecating story that he is dating someone awful, and he asks Marc, “Are there any decent men in this city?” Before Marc can respond, Thomas tells him that he can’t have an opinion because Marc’s “hot, wealthy husband is about to lead a singalong by a roaring fire.”

Advertisement

What follows is The Before, a glimpse of the joyful and colourful life Marc shares with his hot, wealthy husband, Oliver (Luke Evans). There’s laughing and friendship and very nice clothes and a beautiful home and the freedom that exists when you’re married and childless and have exorbitant wealth. But as the singalong begins, as everyone sings “Every day will be like a holiday / When my baby, when my baby comes home,” it foreshadows what the rest of the movie will explore, what happens to Marc and his two closest friends when his baby can’t come home.

Without knowing the fate of Oliver, this seemingly perfect scene could function as the beginning of a cozy Christmas movie, but there are clues that this life, this party, is not only a “shimmering success,” as Oliver calls it, but also a flickering façade. Without giving away the plot, it’s enough to say that the dialogue and actions of the characters are brilliantly written to reveal the discord underlying the charmed life they appear to lead. Dan Levy’s writing and directing set the stage for a complicated grief.

In a movie with grief in the title, it spoils nothing to reveal that The Before becomes The After when Oliver leaves the party in a cab to go to Paris for work. The cab makes it only a block before he’s killed in a car crash. All of this takes place in the first nine minutes of the film in a scene that ends with Marc running toward the sirens he heard from inside his apartment and the flashing blue lights he saw out the window. As he runs down the street toward the accident, the viewer is left looking out the window. The music stops, the image fades and the title “Good Grief” appears on the screen.

This is when The After begins. The next scene opens without music as Marc lies in bed with his eyes closed. His world is deprived of colour. His face is in shadow. As the somber score slowly begins to play, he opens his eyes. What follows in the next 80 minutes is a realistic and intimate portrayal of the messiness of grief that takes place in a highly stylised world (the cinematography, sets, and costumes are beautiful).

From attending the funeral to dealing with the legal and financial logistics of someone being gone to entering a new season (in this case spring) that the person you love will never see and bemoaning the exhaustion and physical toll of grieving while questioning when it’s necessary to stop mourning and start living (in this case dating again), Good Grief portrays absence and the void it creates. This part of the movie, while short, feels weighty and reminds me of Joan Didion’s The Year of Magical Thinking, which chronicles the year after the sudden death of her husband, writer John Gregory Dunne. In the final pages of the memoir, at the end of that first year, she writes, “I also know that if we are to live ourselves there comes a point at which we must relinquish the dead, let them go, keep them dead.”

Advertisement

“What follows in the next 80 minutes is a realistic and intimate portrayal of the messiness of grief that takes place in a highly stylized world (the cinematography, sets, and costumes are beautiful).”

For many, that anniversary is that point. Marc’s friend Sophie (Ruth Negga) says as much at the end of the 14-minute sequence. It’s December again, and she encourages Marc to go out to a party instead of staying at home with a bag of takeout.

“We have been here for you whenever you’ve needed us for almost a year now. We built you the nest, and we sat on you for a year. It’s time to hatch.”

The bulk of the movie takes place after this scene. Marc invites his two best friends, Thomas and Sophie, to Paris, and the pace of the movie slows down to capture the days immediately surrounding the anniversary of Oliver’s death.

Advertisement

This is where the movie gets messy. This is where the complications foreshadowed in the opening scene come to light and where Marc’s grief transforms from a private experience imbued with Didion-like magical thinking to a lived experience with long-term ramifications.

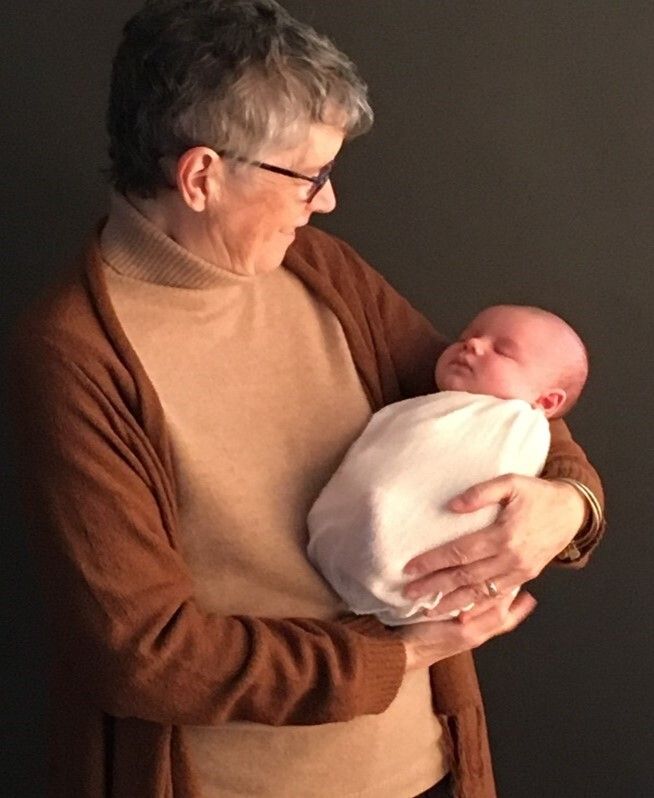

After my mom died, I learned that the transformative power of grief is not only personal but also relational. My mom’s death changed me as much as it did my relationships with the people around me. The closer I was to those people, like my husband, brother and best friends, the more those relationships shifted. This often-unexplored aspect of grief is what I found to be the most cathartic feature of Levy’s movie, and it was especially realistic because it highlighted the characters’ flaws, their imperfections becoming even more noticeable and relatable as they struggled through their grief.

While the film is about Marc’s individual grief, the section of the movie in Paris shows the way that loss ripples outward, complicating his relationship with his best friends, who are facing their own “messy secrets and hard truths.”

I don’t want to spoil what those complications are or where it leads them, but, as someone who also lost a loved one at Christmastime (my mom died 10 days before Christmas), I was grateful for the experience of bearing witness to Marc’s and his friends’ journey out of magical thinking and into the world, especially at a time of year when the rest of the world is bright and festive and joyful.

In a recent interview with NPR, Levy said the movie ”came from my own confusion around feelings of grief and what it all meant and whether I was honouring the people that I was mourning appropriately. In my case, it was my grandmother. And then five days before I wrote the screenplay, my dog of 10 years passed away, and so it was a very raw and confusing time. I couldn’t speak the feelings. I could only write them, and the feelings in it were the only way I could kind of make sense of my own.”

Advertisement

In the immediate aftermath of my mom’s death, I don’t think I would have been ready to watch a movie like Good Grief, but now, five years later, I’m thankful for the honest, raw messiness of it. The film captures both the confusion and isolation of what it feels like to grieve and how that grief can become hope, how there can be a goodness that occurs when we let the dead be dead, even when the relief of doing so becomes its own type of pain and loss.

In the movie, Levy compares that loss to an ulcer in one’s heart that never goes away, and it doesn’t. We always carry our grief with us, but, as his movie shows, it can be transformed into something better, something good.

If you’re expecting a funny, Schitt’s Creek-esque take on grief, this is not the movie for you. But if you are grieving and want to feel like someone out there understands what you’re going through, you can stream Good Grief now on Netflix.